A person's cognitive abilities do not change with age, but does it determine whether a child will become rich or live in debt as an adult? Scientists have found the answer.

Scientists are unusual people. From time to time, they ask themselves questions that seem to have no connection to real life. Some of them may even seem somewhat discrediting to us: when racial or gender differences become the subject of study, a part of society is bound to be indignant. But science, no matter how strange it may seem to us, does not operate in the categories of “good” or “bad”. The goal of scientists is to find out the truth.

One such potentially scandalous study was published last summer in PLOS.

It is based on data collected during the long-term British research project "National Study of Child Development". Back in the 1970s, a group of scientists selected about 6,000 families with children and conducted a study on them. In particular, at the age of 10, the project participants underwent a standardized assessment of cognitive abilities. Over the decades, the initially collected data was enriched with a variety of information about the participants, including during eleven surveys.

This work has become an excellent basis for thousands of scientists, including those whose work we will now discuss.

Smart people don't take out loans?

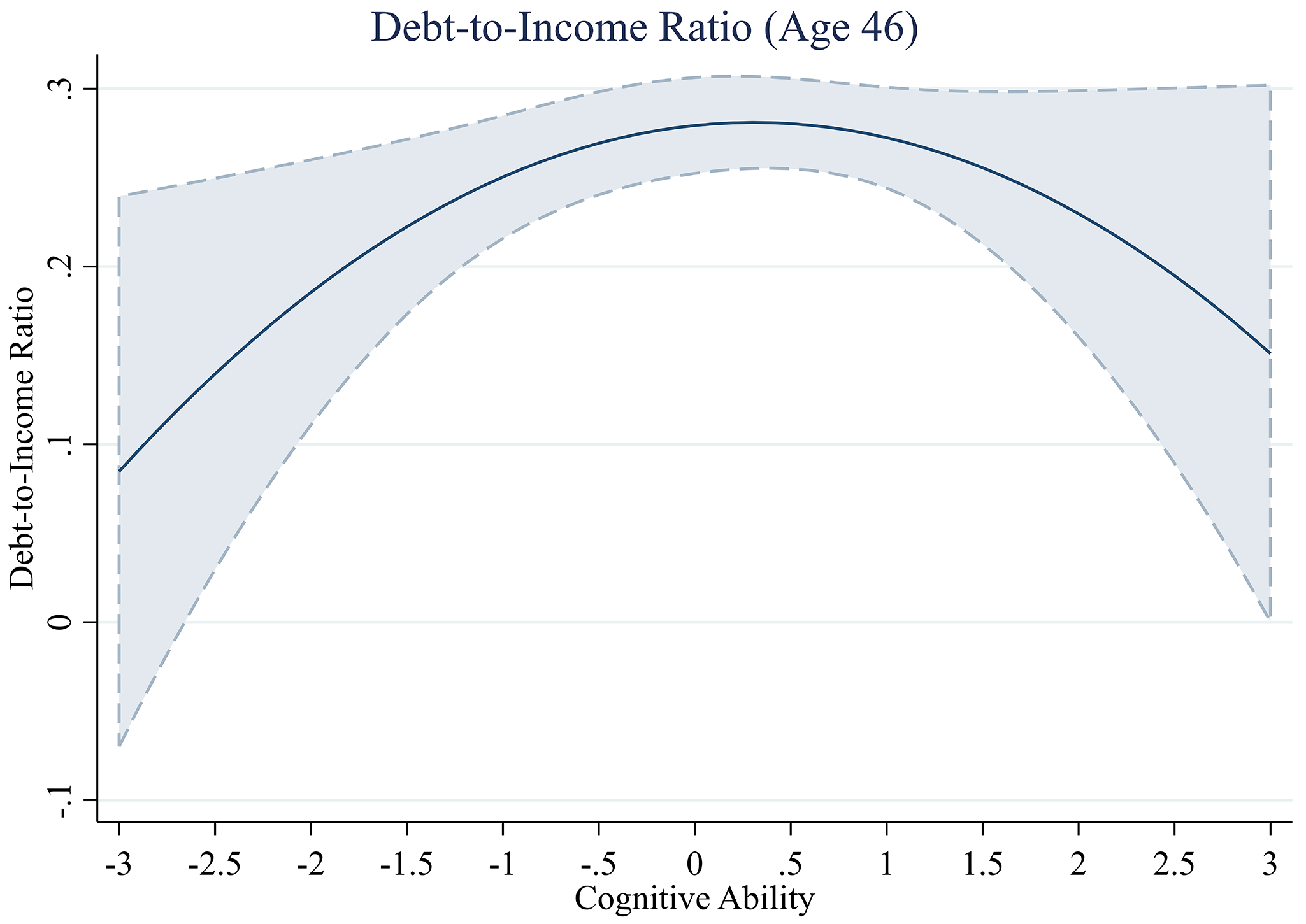

One of the really important discoveries from the point of view of practical application that the scientists managed to make is that the relationship between debt and cognitive abilities is not linear. It turned out that people with the highest and lowest cognitive scores are almost equally indifferent to borrowing. And people with average scores take out the most loans.

If we divide the debt on loans by the respondent's income, that is, we calculate the same debt, then for people with the lowest cognitive abilities it does not exceed 10% on average. For people with the highest cognitive abilities – 15%. And for the "strong average" it touches 30%.

This is not a very reliable conclusion, given the very large range of values obtained, which is indicated by the gray area (confidence interval) on the graph, but even with this caveat, it is clear that people with the lowest cognitive abilities are less credited.

The authors of the study do not provide an explanation for this phenomenon. They did not establish any real cause-and-effect relationships. However, they did offer several hypotheses. For example, the explanation may lie in limited access to credit: such people are less likely to receive higher education, which is included in the calculation of credit risk. Or they themselves try to avoid loans due to the complexity of modern financial products: perhaps, installment payments seem too dangerous to them, again due to their educational background. But whatever the case, the authors of the study write, the conclusion should be useful for financial services regulators and parliamentarians: efforts to overcome excessive debt should be directed at people with average cognitive abilities.

Do smart people save more?

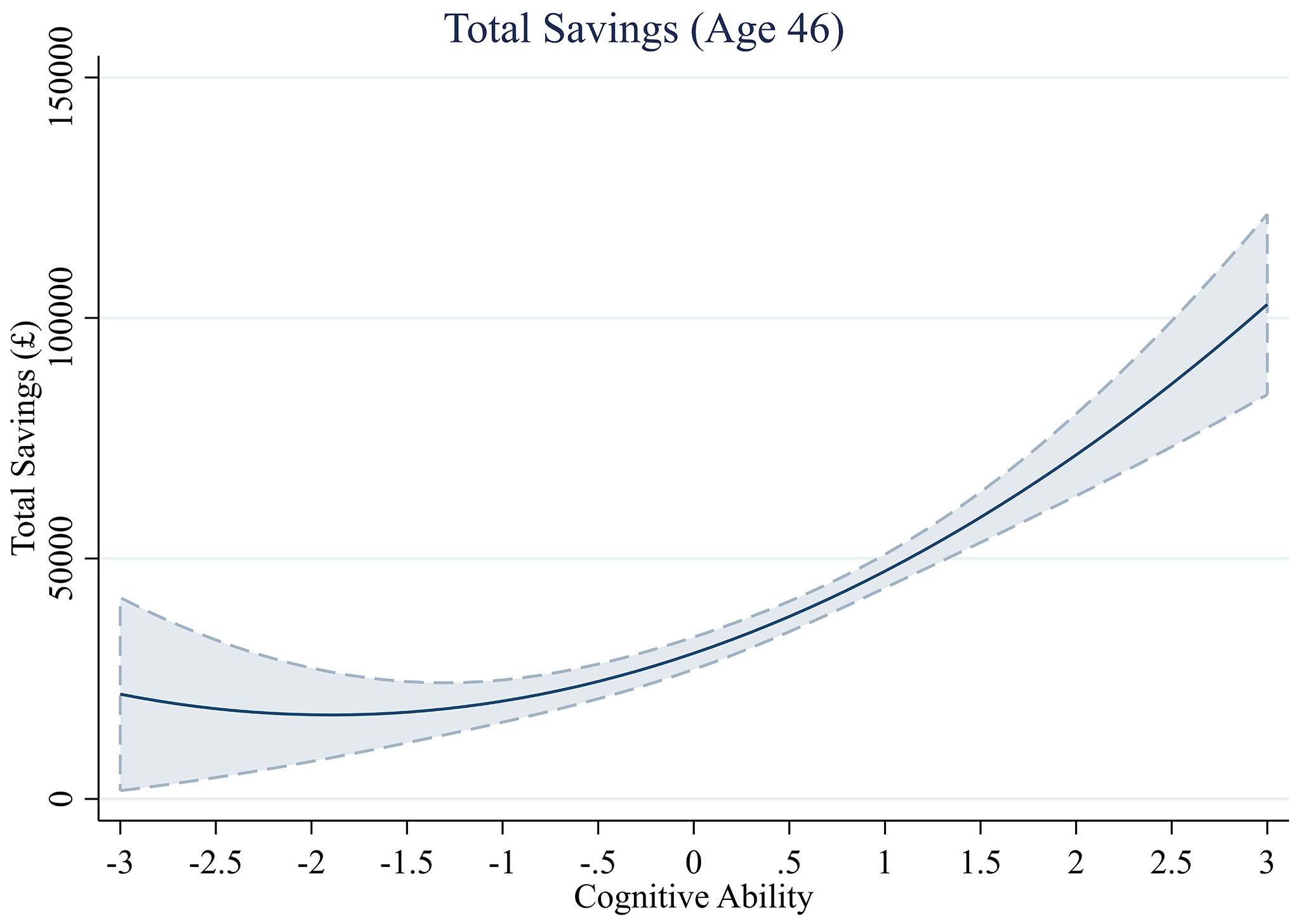

The answer to this question is unequivocal – yes. In all financial matters related to savings, people with the highest cognitive indicators had significantly higher results. They had a fourfold higher absolute indicator of total savings. And with a 90% probability they were already participants in voluntary pension insurance at the age of 42, while at the opposite end of the cognitive abilities scale it did not exceed 50%.

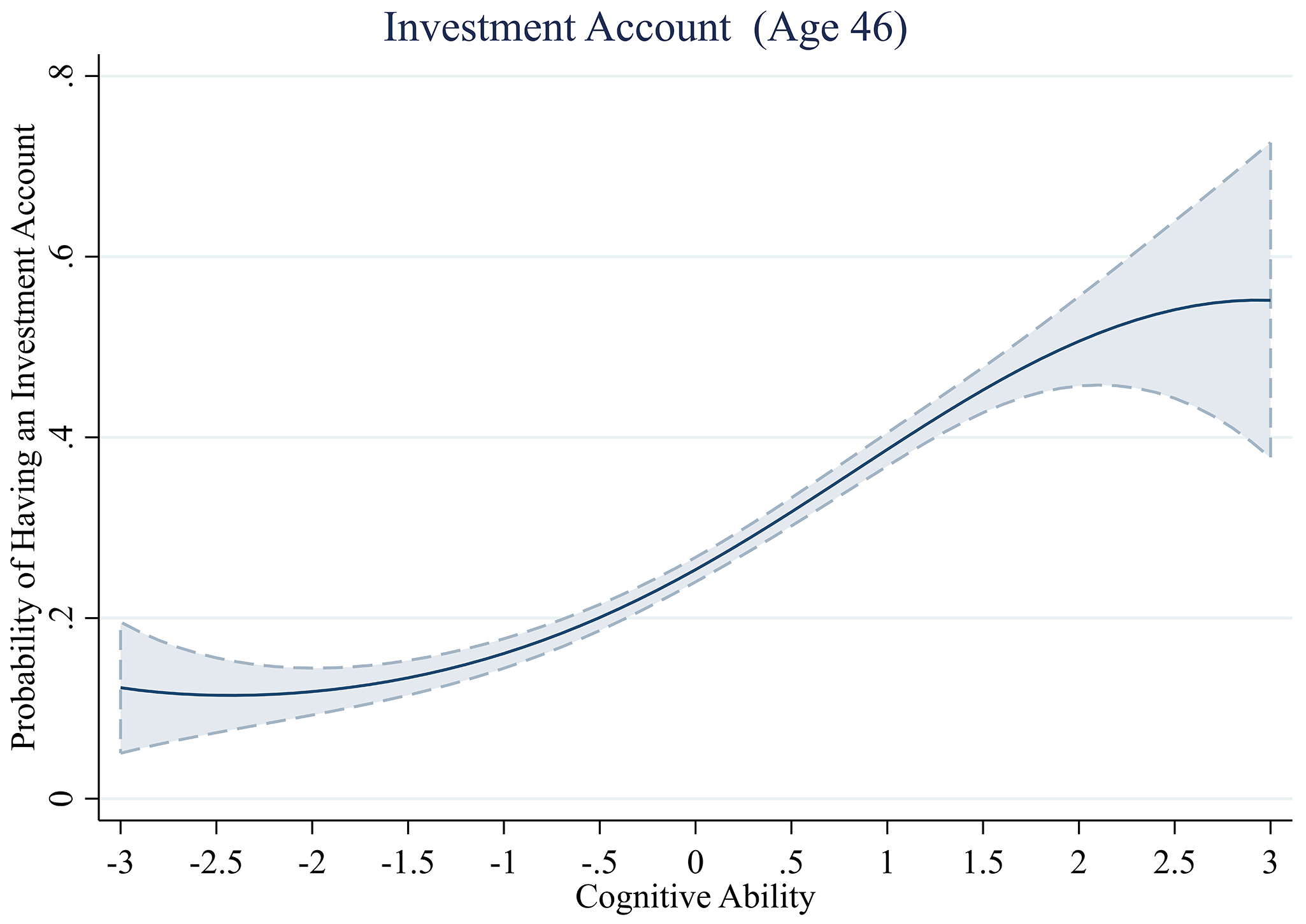

They were also significantly more likely to have an investment account at age 46: 60% versus 10%.

The explanation for this observation may lie not only in the level of education. But also in the general level of income. Obviously, saving money and looking for ways to invest it is much easier when you have it. Moreover, the authors of the work note that the indicators were very significantly influenced by the level of financial well-being of the family when the child was included in the study at the age of 10.

Are smart people less nervous?

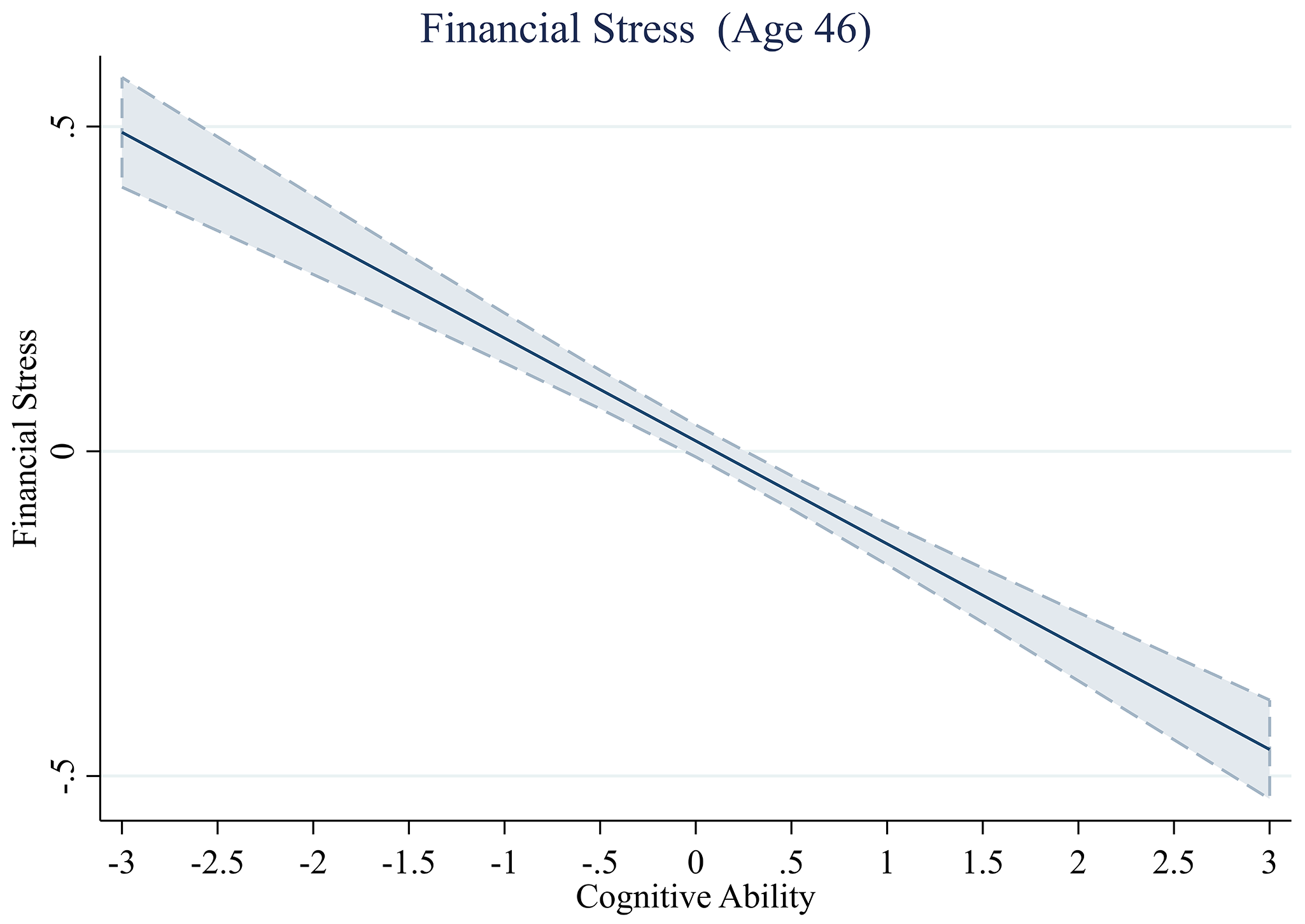

All of the above conclusions can be ignored to some extent. Financial literacy can be developed if desired, and it is also easy to open an investment or retirement account. But what is really important is the subjective feeling of financial well-being. In this case, the criterion for measuring it was the feeling of financial stress: how “painfully” people experience a lack of funds.

The authors of the study found no correlation between cognitive abilities and financial difficulties. That is, they occurred with approximately the same frequency in all study participants. But people with lower cognitive scores showed radically higher levels of stress than participants with the highest scores. This is probably due to the lower level of savings as an airbag. Perhaps with general self-doubt.

What's the point?

First of all, I would like to point out that we should be very careful when using the terms “highest” and “lowest” cognitive abilities. The study included completely healthy children, so we should not exaggerate either the upper or lower limits of these concepts.

In addition, it is worth considering the significant influence of the family on the results of a child's financial well-being in adulthood. Most likely, it is not so much about the amount of money at home, but about the basic financial skills that a child learns from his parents.

If you take even a little care of your child's financial literacy, teach them to save, manage their own money, and talk about complex financial matters in simple language, you can lay a good foundation for their future financial well-being. You probably won't be able to raise a financial genius, but healthy financial habits will definitely not be superfluous in adulthood.