“Money doesn’t buy happiness,” millions of people assure us every day, refusing to acknowledge the dominant role of money in the world. But research refutes this thesis: the level of happiness depends on the amount of money – it has been proven by science.

In 2010, Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton of the University of Pennsylvania published a seminal paper that used empirical data to show a direct relationship between American household income and subjective happiness. They found that happiness increased linearly as household income increased. But after they reached $75,000 a year, happiness levels plateaued. Further affluence did not bring additional happiness points.

For a long time, this work remained a kind of benchmark in the eternal question. Over the past 13 years, Kahneman and Deaton's findings have been cited in 273 other academic papers. But in 2021, they were called into question. Matthew Killingsworth, a colleague of the Americans from the same University of Pennsylvania, analyzed more than 1.7 million reports covering a sample of 33,391 employed American adults and concluded that the subjective level of well-being directly depends on the level of income. And there are no plateaus after reaching the level of $ 75,000 or any other mark. In other words, the more a person earns, the happier he feels.

What is happiness?

In their work, Kahneman and Deaton measured “happiness” using questionnaire data from the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index. The overall score was based on two criteria: emotional well-being and life evaluation.

By emotional well-being, they meant the quality of a person's everyday experience - with what frequency and intensity a person experiences familiar feelings, such as joy, stress, sadness, anger. That is, those that ultimately make a person's life pleasant or unpleasant.

Life assessment is a person's purely subjective opinion about their life.

Killingsworth relied on subjective well-being ratings, which he derived from people’s responses to the question “how are you feeling right now,” which they answered on their smartphones three times a day for several weeks. The response scale started with “very bad” and ended with “very good.”

Who is right?

The dispute was put to rest only this year: on March 1, one of the most authoritative interdisciplinary scientific journals, PNAS (The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences), published a joint paper by Kahneman and Killingsworth, in which they reached a single conclusion, revealing the exact reasons for their disagreements.

There were a lot of the latter. For example, it turned out that the often cited threshold of $75,000 is a very conditional limit and needs to be corrected. First, there was no exact number in the surveys in which the data was collected. Participants were asked to estimate their family income in ranges. One of these: from $60,000 to $90,000. Second, due to inflation, the dollar has depreciated over the past 10 years. Therefore, a new hypothetical level of American happiness was recognized as a family income of $100,000 per year.

In addition, the measurement design used in the first study was such that it measured the depth of unhappiness rather than happiness in general. Killingsworth used a completely different approach, collecting more in-depth data using a mobile application. This allowed him to build a scale in two ranges at once: unhappiness and happiness. When the efforts of scientists were combined, a solution was found. Which, by all indications, will become a new standard for many years.

So is happiness in money or not?

I sincerely apologize for the long introduction - it is important for understanding the issues, disagreements, and the essence of the key conclusion. Or rather, several conclusions at once. It is time to move on to them.

1. The level of happiness is clearly and reliably correlated with the level of income. Moreover, up to a certain level (in the aforementioned studies – $100,000), the linear relationship is absolutely the same for all categories of the population.

Considering the spending structure of the average American, it is not difficult to conclude that it is also fair for Ukrainians. In other words, people feel happier as their incomes grow, at least until they reach a level that covers basic needs with a small margin: comfortable housing, their own car, access to food without noticeable restrictions, sufficient time and level of leisure, and a good education for their children.

2. But for the least happy people, this connection is lost after the specified level. In other words, basically unhappy people become happier as their income increases. But when all key needs are satisfied, there is no further increase in the level of happiness. The reason may be that such people either do not know how to be happy in principle, and therefore, by covering up the key causes of their unhappiness with money, they lose progress. Or they simply do not understand how to transform money into happiness.

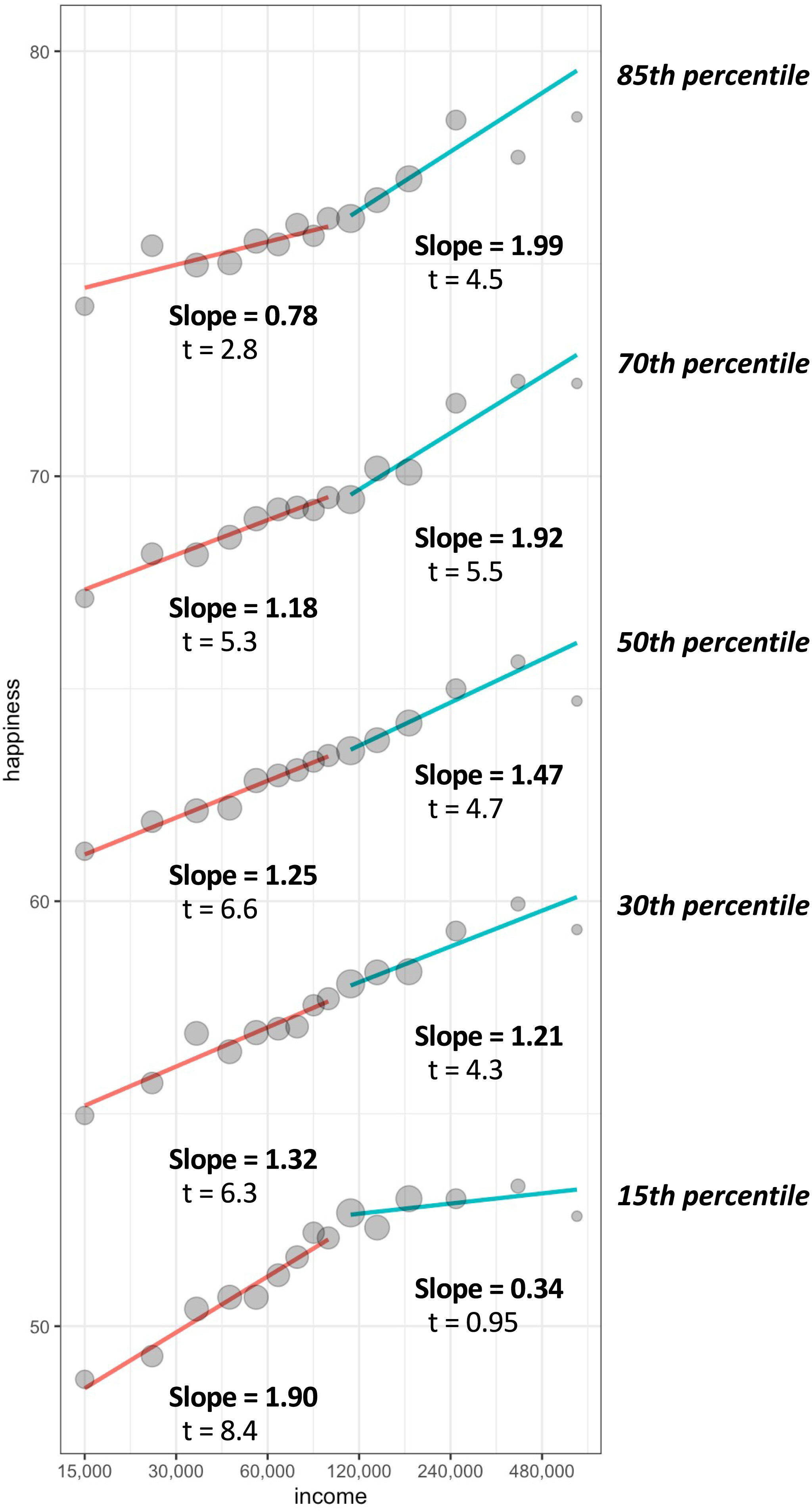

3. The happier the respondents were at baseline, the stronger the link between further income growth and feelings of happiness. The dynamics of happiness growth even accelerated significantly for the 15% of people who were in the group of the most basically happy.

So who is right in the end?

I understand that you would like to hear a more specific answer. But, unfortunately, there is none. Yes, according to research, the feeling of happiness depends on the amount of money. However, if you feel like a deeply unhappy person in principle, an increase in salary will make you happier (or happier) only for a certain time.

If you can find joy even in the face of a constant shortage of money, its infinite increase will theoretically make you infinitely happy (or lucky). So, in the end, everything comes down to the eternal dilemma of “are you an optimist or a pessimist?”

And yet, it has now been scientifically proven: money definitely brings happiness.