Against the backdrop of the latest news about the introduction of a new American tariff of 20% for the European Union and the negative consequences of this (in particular, due to a possible recession and rising inflation), the topic of poverty among the European population has again arisen. Everyone understands a simple linear relationship: the worse the economy develops, the more the poverty level in the EU, which Ukraine is entering, will grow. That is why there are growing fears among Ukrainians about the deterioration of living standards by the time we become part of the European Union. But is it really worth being afraid? Let's look at the numbers.

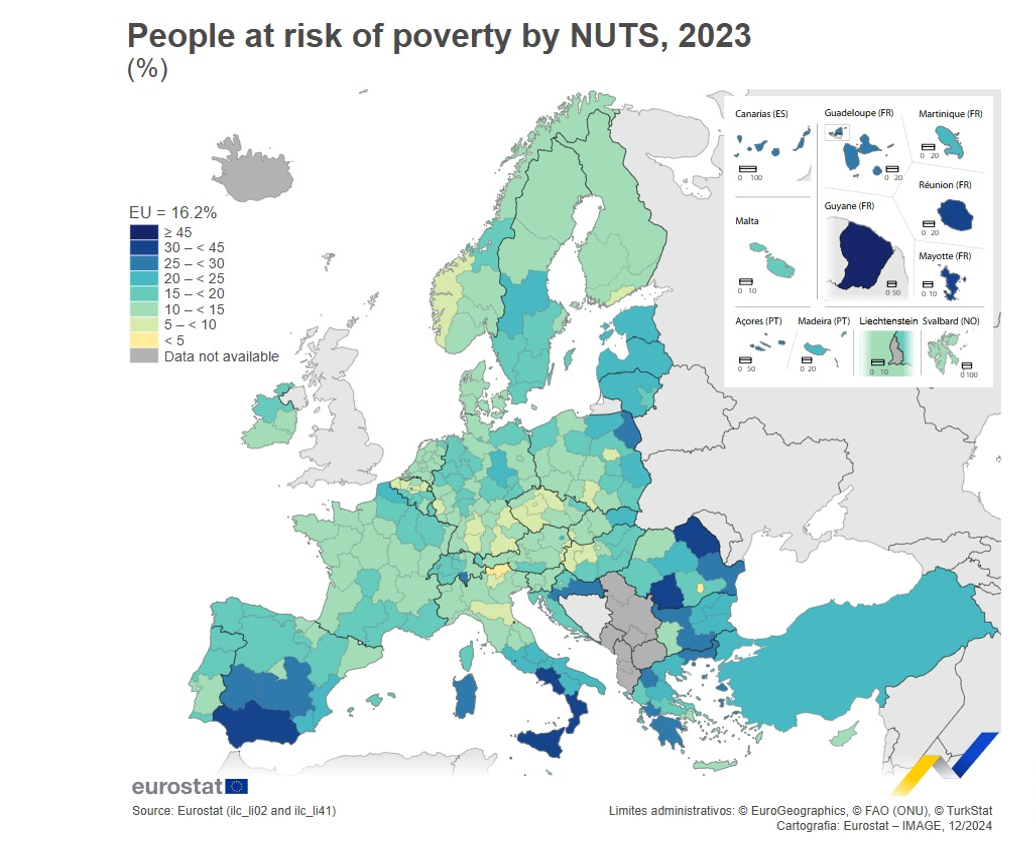

European analysts have not yet compiled reports for last year, but there is Eurostat data for 2023. From them we see that even then about 16.2% of the European Union (which is 71.7 million people out of 442 million) were at risk of poverty. The poverty level was calculated using national poverty thresholds in each country separately.

At the regional level, only 10 regions across the EU had a share of people at risk of poverty exceeding 30%. The highest rate was in the outermost region of France, Guiana, at 53.0%, as well as in the Italian regions of Calabria (40.6%) and Sicily (38.0%). At the same time, in 26 regions of the European Union, only 10% of the population was at risk. Examples were given from the Romanian region of Bucharest-Ilfov, where this figure was only 2.1%, as well as the Italian province of Bolzano/Bozen (3.1%) and the Belgian province of East Flanders (5.4%).

Eurostat analysts even drew a map to make it clear where in the EU the risks of poverty are the highest/lowest.

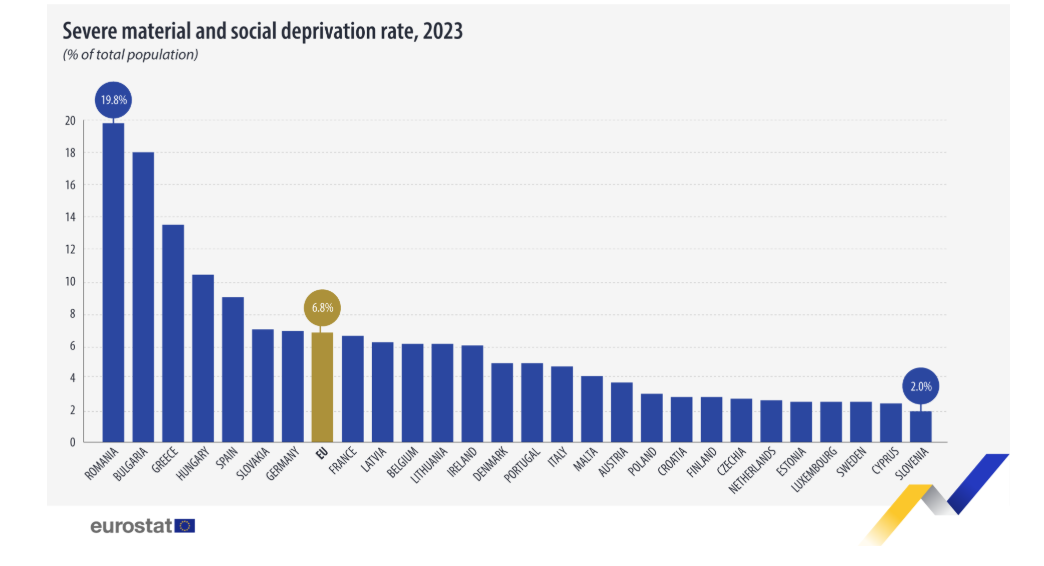

Eurostat also calculated that 6.8% of the EU population faced serious material and social threats, which is slightly more than the 2022 figure of 6.7%. This is not poverty, but economic hardship. The worst cases were recorded in Romania - 19.8%, Bulgaria - 18.0%, Greece - 13.5%, Hungary - 10.4% and Spain - 9%. And the best - in Slovenia (2.0%), Cyprus (2.4%), as well as in Sweden, Luxembourg and Estonia (all 2.5%).

The highest echelons of the EU have repeatedly emphasized that combating poverty is one of Europe's priorities. And economists have introduced several different assessments and indicators in this regard, in addition to the "risk of poverty."

The term "material and social deprivation" is used, which includes 13 criteria. These include: the ability to pay for unforeseen expenses, annual leave, regular consumption of meat or fish, home heating, car ownership and access to the internet. People/families who cannot afford 7 or more items from the list are considered to be in a state of severe material and social deprivation.

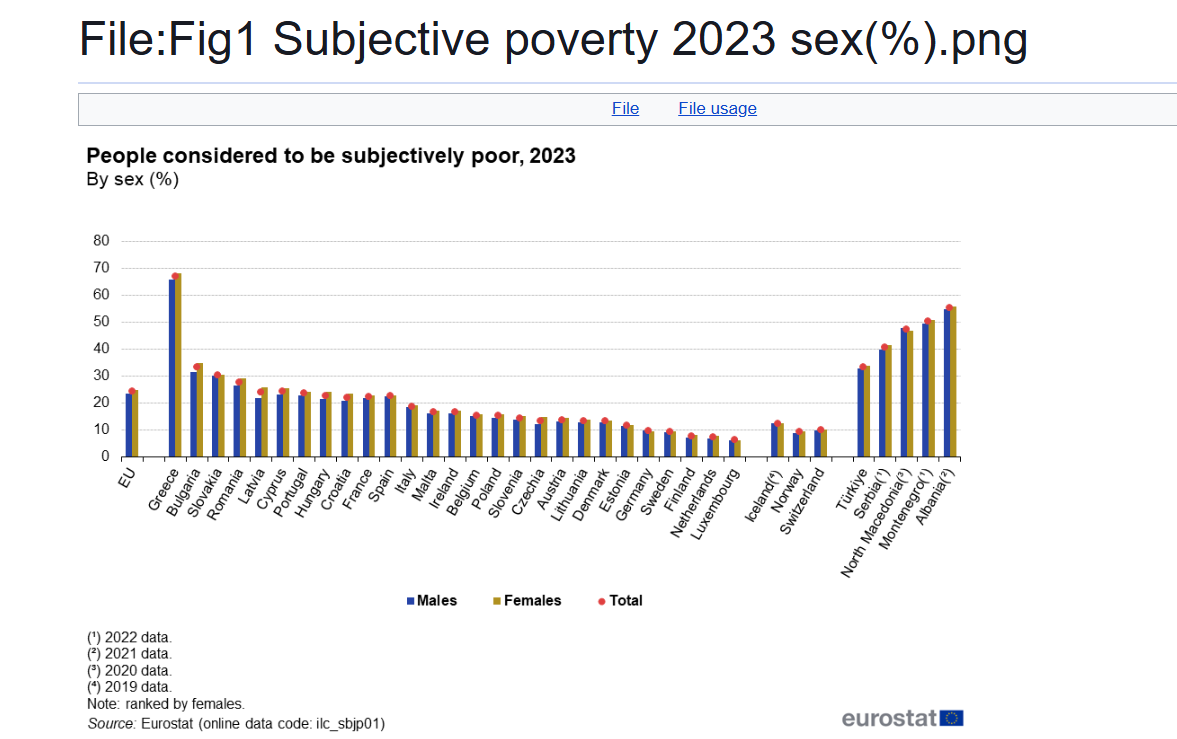

Another indicator, which is newer, is “subjective poverty”. This is a concept developed from the EU-SILC variable, which describes the ability to “make ends meet”. The assessment takes into account the material well-being of the household, including income, expenses, debts and wealth. The EU-SILC variable has 6 response categories:

- With great difficulty.

- With difficulty.

- With some difficulty.

- Quite easy.

- Easy.

- Very easy.

A household that answered “With great difficulty” or “With difficulty” is considered to be in “subjective poverty.” This approach is more conservative than one based on a question of minimum income (or the lowest income to make ends meet).

According to Eurostat, in 2023, 24.1% of the population in the EU was subjectively poor, which is 0.7% less than in 2022. There were fewer of them (23.5%) among men and more among women (24.7%). The highest subjective poverty was in Greece (67%), Bulgaria (33.2%) and Slovakia (30.3%). And the lowest in Luxembourg (6.2%), the Netherlands (7.3%) and Finland (7.5%).

Not the best, but still good indicators were recorded in Germany (9.7%), average ones in the Czech Republic (13.4%) and Poland (15.1%), where the largest number of Ukrainian refugees currently live.

As they say, one should not confuse tourism with immigration, but immigration with refugee status. After all, during the time of danger, no one studied these rather interesting studies for ordinary people who want a better understanding of the situation in Europe from the series “where people live better”. Ukrainian refugees who left their homes because of the war rarely went to the Netherlands or Finland, where the smallest number of “subjectively poor” people live. Among the EU countries that have accepted the largest number of our people, Germany (1.1 million refugees or 26.9% of the total number in the European Union), Poland (979.8 thousand or 23.3%) and the Czech Republic (378.5 thousand or 9%) are not the richest in terms of the subjective feelings of the population. The people of these countries sheltered such a number of Ukrainians in their homes not because they felt rich enough for this, but because they have a great good heart.

Be that as it may, this information remains interesting for both specialists and ordinary people, because there is a demand for it: European “poverty” is constantly being researched. Interesting conclusions were recently announced by specialists from Oxford University, who were based on data from the Luxembourg Income Survey (LIS) from 1986 to 2019. That is, the growth of poverty was studied in dynamics, and the increases can be estimated from aggregated data.

Oxford scientists have proven to government officials who insist that poverty can be overcome primarily through job creation and increased employment rates that this alone is not enough. To lift people out of poverty, they also need to provide them with decent wages and benefits. It would seem that this is an obvious and understandable truth, but officials and employers can only be truly convinced by data from rigorous research from reputable scientists.