On September 4, the Center for Economic Strategy presented a major study, telling about the life of Ukrainian refugees abroad. This is not just idle curiosity. The results of the researchers' work have quite practical application. After all, without understanding the realities of Ukrainians who find themselves abroad, it is impossible to build a strategy for their return.

To return or not

In Ukrainian society, among those who have already returned to Ukraine or did not leave it at all because of the war, one can often hear the opinion that the intention to return forced migrants to their homeland is futile or even harmful. Some consider them to be something like traitors. Others are somehow sure that those who have remained abroad are mostly those who simply do not want to work and are taking advantage of the generosity of European taxpayers.

There is probably some truth in these words. With a 100% probability, out of the millions of Ukrainians currently abroad, there will be at least one or two who accurately correspond to the above theses. But the results of the study completely refute them and prove that the return of Ukrainians to their homeland should be one of the priorities not only of the state, but also of each of its citizens. Why? Listen to the numbers.

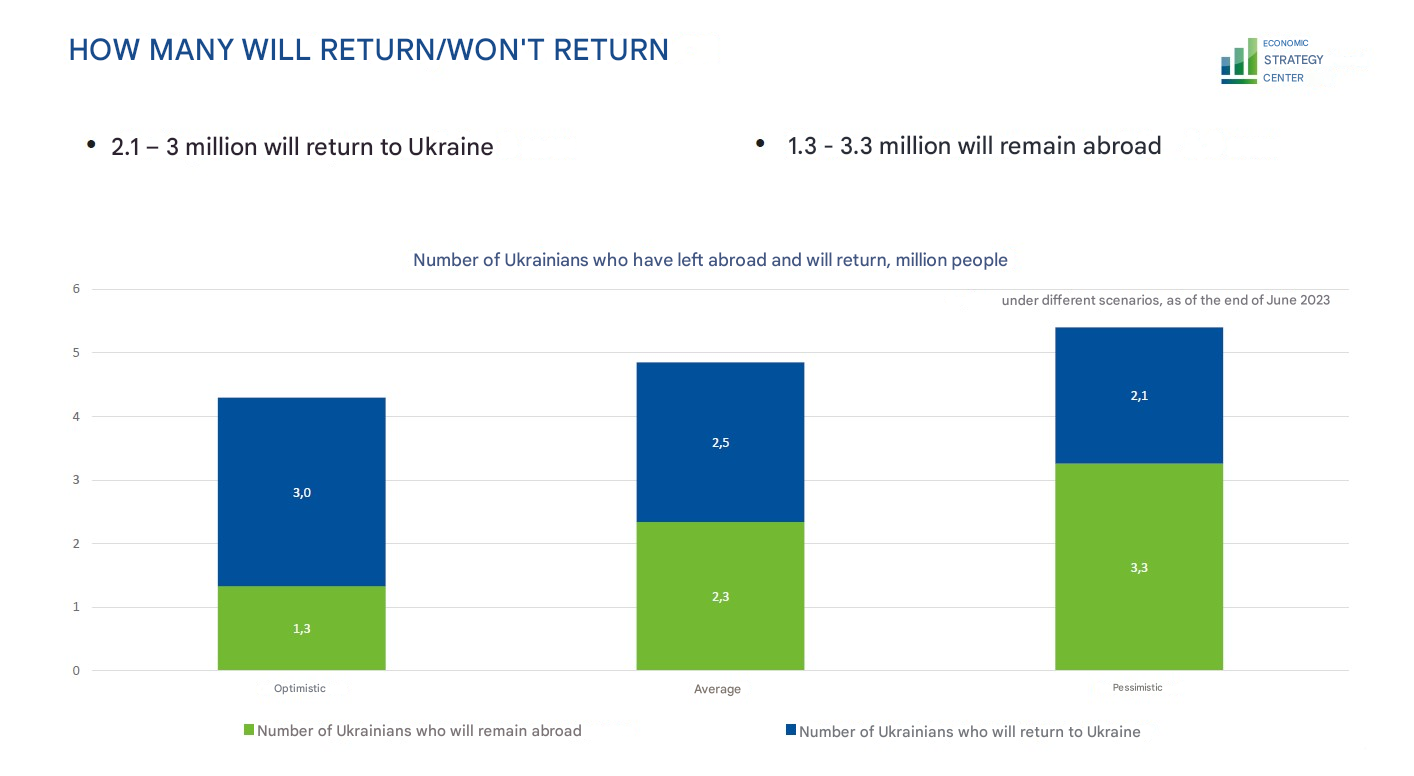

According to the study, under a pessimistic scenario, out of about 6 million Ukrainian refugees, about half will not return to the country. The direct economic consequence of such a scenario is a loss of 6.9% of GDP each year. Even under an optimistic scenario, according to which only 1.3 million refugees will remain abroad, the potential GDP loss is estimated at 2.7% of GDP.

One can argue with these estimates. In the end, they may turn out to be either overstated or overly optimistic. But the fact is undeniable: the economy is about people.

Data and graphics - Center for Economic Strategy

One step away from demographic catastrophe

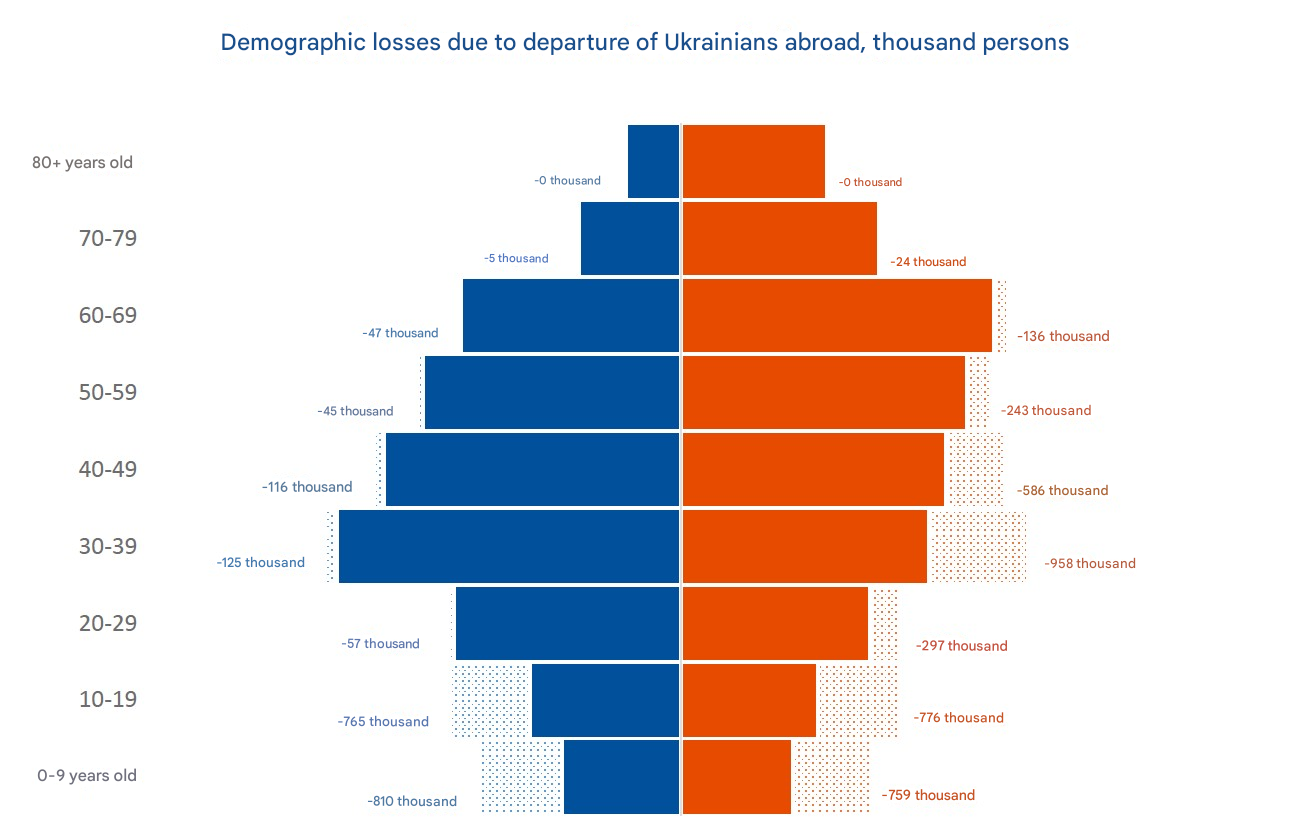

Let's take a look at who is abroad. The vast majority are economically active Ukrainians of working age and their children.

According to the study, approximately 25% of forced migrants are classic refugees: mostly middle-aged women with children. Another 29% are a strong middle class: people who held managerial positions in Ukraine, were professionally successful, or had their own businesses. Another 29% are the so-called quasi-labor migrants: those who were thinking about going abroad in principle, are ready to work there, and are very well adapted to life in a foreign country. The remaining 16% are people who ended up abroad from combat zones. Most of them have lost everything they had. And although they are probably the most difficult to adapt to new living conditions, they are the ones who have the least incentive to return to Ukraine, because they have lost their homes.

And let there be no illusions: 63% of Ukrainian refugees have higher education. For comparison, the average figure for EU countries in 2021 was 41%.

But even more worrying are the demographic figures. Of the approximately 4 million refugees living in the EU, 1.4 million are children under 17. Another million are young people aged 18 to 34. The largest group, accounting for more than a quarter of the total number of refugees in the EU, are working-age women aged 34-64.

If we compare these data with data on intentions to return to Ukraine, it becomes clear where the terrifying figures of GDP losses come from. The absolute majority of those who doubt returning to their homeland are young people under 39. The worst situation is among adolescents aged 14-17. In this group, you need to look with a microscope for potential repatriates.

Data and graphics - Center for Economic Strategy

Let's ignore the theoretical losses of human capital. Let's just look at the situation with pension provision. In 2020, 19% of all State Budget expenditures were intended to cover the deficit of the Pension Fund. In absolute figures, about UAH 200 billion of taxpayers were directed to this, in addition to direct contributions to the Pension Fund.

According to the State Employment Service, at that time in Ukraine, the number of employed people aged 15-70 was about 16 million people. It was they who took on the obligation to pay pensions. Subtract from this 2-3 million people who did not return, those who died defending Ukraine. Draw your own conclusions, as they say.

School, parks, medicine

The authors of the study not only ask questions, but also give very specific answers. Advice that can help refugees return to Ukraine. The share of those who still have such an intention is constantly decreasing and is now about 41%. So it is worth at least taking a look at them.

The biggest problem is overcoming security risks. Simply put, most Ukrainians are deterred from returning by war and rocket attacks. Life abroad is not easy, but still, running around at night in basements and bomb shelters for many of those who are abroad is a much worse alternative. In this direction, of course, the Ukrainian people and authorities are doing the impossible.

The second big problem is the loss of housing and jobs. Such people need to be provided with conditions for return, provided with housing, assisted with employment, retraining, and integration into social life in new cities and towns. This is an extremely difficult and complex task.

I would like to mention one more area separately – assistance to Ukrainian children, especially high school students and students. Most Ukrainian children abroad study in local schools. Some are also trying to introduce the Ukrainian curriculum, but it is becoming increasingly difficult to do so due to the increased requirements for full-time education in Ukraine.

Special conditions should be created for all such children. On the one hand, to give them the opportunity to listen to the Ukrainian program, at least in a condensed form. Currently, such an opportunity is provided mainly by private Ukrainian schools, which not every family can afford. On the other hand, to recognize their foreign education and not require them to pass any exams. Those who return to Ukraine as schoolchildren should be helped to integrate into studying in Ukraine, without demanding the impossible. Those who come as applicants should be allowed to enter universities using a simplified procedure. By the way, this is also mentioned by the researchers in their conclusions.

To many, this approach may seem unfair. Why don’t children who hid from rocket attacks, studied by candlelight and in winter jackets have the same preferences as those who studied in warmth and comfort? Such a question, of course, has the right to be voiced. But if we want to return children and their mothers to Ukraine from abroad, we should look a little deeper and see “growth points” instead of “problems.”

After all, these children are not just percentage points of GDP. They are a vaccine of humanity, justice, democratic values, and liberal views for all of Ukraine. And they are also a bridge to Europe, a connection with it, because these children are future adults who have managed to learn languages, make friends, and understand the European mentality. And these skills and knowledge acquired by children are Ukraine's opportunities for more successful business and easier access to foreign markets in the long term.